(NB This is an essay commissioned for an art catalogue accompanying Bracha L. Ettinger’s ‘Bracha: Pietá – Eurydice – Medusa’ exhibition at the UB Anderson Gallery, Buffalo, NY, 2018. The essay published here is awaiting publication in the gallery art catalogue which will feature an essay on Ettinger’s notebooks by Dr Amelia Jones)

———————————————————————————————————————————–

by Tina Kinsella

‘Measures against Feminine Excess’

If he kills you, I shall no longer be able to weep

over your bier, dear child, whom I myself begat

(Illiad: 22.86-87)

In an act of creative transgression, Bracha Lichtenberg Ettinger’s artistic practice and process blurs discrete divisions between painting, psychoanalysis and theory. Her artistic practice discloses a radical aesthetics that re-paints the relationship between collective and individual trauma, cultural history and memory. This aesthetics is announced in using her first name as artist’s name: a Hebrew word bestowing the authentic meaning of “blessing” that alerts us to the compassionate, even spiritual, intervention the artist can make in our conceptual framings of the world. From this perspective, the painter and theorist is considered as an artist, first and foremost, who solicits us to enter into an inner space of painting that reanimates aesthetic affect to rehabilitate our ethical sensibilities and foundationally recalibrate our understanding of the human being.

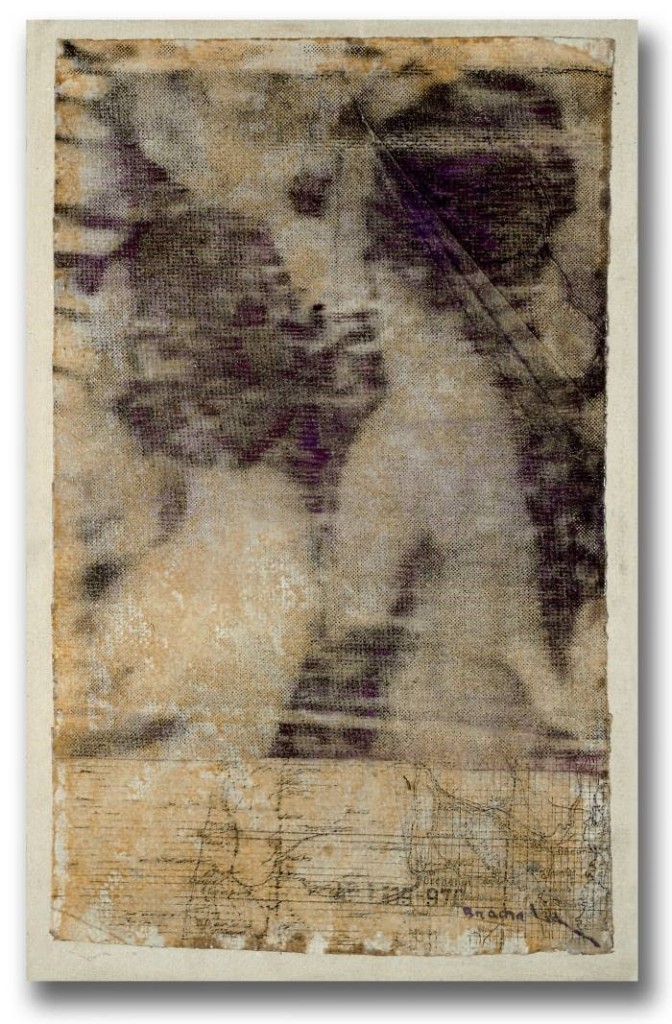

Bracha’s Eurydice paintings suspend this tragic figure at an abysmal threshold between life and death, between disappearing and re-appearing, between annihilation and redemption. These paintings contain inscriptive fragments from the artist’s family archives and photographic documents of the Holocaust which are traced with bands of oil paint mixed with the powdered ash of photocopying dust. One particular photograph appears again and again in this series of paintings; it depicts a group of women moments before their impending death at the hands of Nazi Soldiers during the Einstatzgruppen murders in the territory of the Soviet Union in the early 1940s. In this photographic image, a woman is looking towards her soon-to-be assassins; the face of another woman is turned toward the photographer, and us, in silent appeal; and yet another woman looks down at the naked child in her arms that she is unable to save. This photograph, other images and fragments are passed through the blind gaze of the photocopier. The copying process is halted mid-way so that the documents are rendered incomplete, unstable, malleable, yet hospitable to the touch of the artist’s hand which then applies, rubs-off, re-applies layers of paint as colour glazes, wounding lines, sorrowing colours, sometimes over many years. Colour-swaddling the traumatic photograph with diaphanous bands of violet, black, white, sometimes crimson, the slow labour of the artist’s painterly gesture binds Eurydice to the women and child held, helplessly, in its mother’s arms in a continual movement of infinite becoming. Eurydice does not appear within the canvas, we cannot capture her with our gaze, she is not an object of representation. Rather, we wait and tremble with her in the porous field of painting-encounter that Edmond Jabès has termed ‘the threshold where we are afraid’.[i]

History does not end with our post-traumatic era, as some would claim. Rather the aesthetic encounter with the artist’s image extends a delicate provocation, as supplication, to remain within the quivering, fragile threshold where history may commence in tender perpetuity.

The artist returns to the movement between trauma and healing revealed in this series in her recent oil paintings where literary, mythic and biblical figures conjoin with the tragic Eurydice, whether she is named or not. Whilst the earlier Eurydices were executed through a combination of oil paint, photocopic dust and mixed media, these more recent works move more firmly towards the direct application of oil paint to the canvas in works such as Eurydice No. 51 (2012-16), Eurydice No. 52 ― Pietà (2006-2012), Eurydice No. 53 ― Pietà (2006-2012) and Pietà no. 1 (2013-15). These paintings continue Bracha’s project of compassionate lamentation, reminding us of the distraught, sorrowing mother who holds her beloved, dead son in her arms in the Pietàs of Michelangelo, Giovanni Bellini, Luis de Morales and El Greco. The foreshortened perspectival space, huddling figures, ominous shadowed sky and steely blue tones infusing the pearlized skin of the dead Christ’s body in El Greco’s Pietà (1578-1614) both conduct and amplify the air of abject, oppressive despair that permeates this image depicting the loss of a singular son. It is as though one gazes upon a private scene: there is uncertainty as to whether one is implicated in the aftermath of violence as witness or voyeur. However, in Bracha’s works containing the same name, darkness is transformed to emanating light that creates a portal for entry for the viewer-as-participant. Strobes and whorls of pearly lilac-blush oil paint glaze as skin stretched over the entirety of the canvas, which is rendered porous. The singular loss conveyed in the El Greco Pietà is stretched, multiplied and finally dispersed across and between canvases so that one no longer observes a site of solitary mourning, but rather is ushered into a space and time for lamentation that enlaces past, present and future in an elegiac movement that unfastens the armoured gaze of the eye to solicit us at the seat of our capacity for mercy, and perhaps even elicit hope.

[i] Edmond Jabès in conversation with Bracha L. Ettinger (1993). ‘A Threshold Where we Are Afraid’ in the Museum of Modern Art, 1993.

Fig.1 Eurydice No. 2 (1992-1994)

Oil, Xerography, Photocopic Pigment and Ashes on Paper Mounted on Canvas

Bracha L. Ettinger

Fig. 2 Eurydice No. 51 (2012-16)

Oil on Canvas

Bracha L. Ettinger

Fig. 3 Eurydice No. 52 – Pietà (2006-12)

Oil on Canvas

Bracha L. Ettinger

Fig.4 Eurydice No. 53 – Pietà (2006-12)

Oil on Canvas

Bracha L. Ettinger

Bracha’s recent paintings beckon us to reprise the work of mourning, to return to the grounds from which the act of lamentation arrives and to reappraise the particular emotion that labouring through grief produces. In Mothers in Mourning, Nicole Loraux observes that in ancient Athens ‘the lament of mourning’ was considered an excess of “páthos”. This word deriving from the Greek pathein “to suffer, feel” and penthos “grief, sorrow”, quite literally meaning “what befalls one”, refers then first to a quality that arouses pity or sorrow which emerges as a result of suffering or calamity. Whilst in contemporary usage, páthos implies the incumbent poignancy of piteous sorrowing. Páthos seems to imply an effect that is produced by being affected by something, or someone. And, in this sense, páthos also emits and transmits an aesthetic quality that is perhaps best expressed in the French pathétique, implying emotional registers of delicacy, sensitivity, susceptibility and sensibility that are tinged with tragedy, sadness, even regret. For the Ancient Greeks, however, páthos was considered a curiously “feminine emotion” that was delimited in law, confined to the domestic sphere and subject to regulation at private funeral ceremonies. Banished from public life, ‘hermetically sealed inside the house’ lest it contaminate the city state to pollute, and thereby feminise, the body politic, the prohibition against this feminine sorrow not only subjects the grieving labour of women to state governance, it produces a repressive structure against the expression of such ‘femininity among males’.[i] This injunction against lamentation and the emotion of páthos it provokes bore most pertinence, Loraux muses, when ‘the mourning woman is a bereaved mother who weeps over her son’.[ii] In a cyclical motion, the symbology of Medieval and Renaissance artistic depictions of the Pietà move from the loss of a singular mother’s son to perturb reflection on one’s personal experience of grief before finally returning as a universal representation of mourning now enshrined within religious doctrine. The grief of the mother is subservient and sublimated in the service of spiritual devotion to the Law that God the Father bestows on Mankind. However, as the Greeks knew, the emotion of páthos is always, already a surplus, en plus, which is why it was relegated to the domestic sphere and confined within ritual and ceremony. As the Greeks also understood, the bond between mother and child poses the singular most treacherous menace to the functioning of the state. And so, the Pietà always threatens to disclose this excess of sorrow by surfacing the penumbra of future loss that lurks in the heart of the maternal relationship between mother and child.

[i] Nicole Loraux (1998) Mothers in Mourning. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, p. 11, p. 24 and p.25.

[ii] Ibid, p. 25.

Fig. 5 Pietà (1498-99)

Marble

Michelangelo Buonarroti

Fig. 6 Pietà c. (1505)

Oil on Panel

Giovanni Bellini

Fig. 7 La Piedad (16th Century)

Oil on Panel

Luis de Morales

Fig.8 Pietà (1578-1585)

Oil on canvas

El Greco

Whilst the opalescent Pietàs of Bracha do not entrap the mother and child relationship within any particular religious iconography, they do invoke the dolor that gnaws at the heart’s core of the maternal bond and the most secret of all fears of a mother. They evoke the unspeakable lamentation that takes place at the untimely death of a child, the surfeit of sorrow that is experienced at the loss of one’s own mother. The sorrowing mother here is Rachel, Eve, even Lilith. She is also the Jewish Eurydice caught holding her infant to her breast moments before death who, in the paintings, is aspiring for light at the depth of darkness. But, in addition, she is a codex for and indexical link to the capacity in the human to grieve for horror, terror, suffering that one did not experience oneself: that capacity within the human subject to extend its aesthetical, ethical and affective tendrils beyond oneself to sorrow-with past, present and future others in the world, before, as now, and yet to come.

I have elsewhere connected these later oil paintings by Bracha, in terms of the question of light, to M. W. Turner and Claude Monet’s meditations on light and colour.[i] Turner’s visions of light, lakes, seas and stilled water in Norham Castle (c. 1845), Buttermere Lake (c. 1797–1798), Virginia Water (1830) sit alongside the increasingly turbulent waters in Bell Rock Lighthouse (1819) and Bamburgh Castle (c. 1837). In all of these works, air is always part of his water shapes. Air and water open routes of access to the inner content of the painting and they connect with the rivulets of opalescent light-water in Claude Monet’s late Water Lilies, painted when he was almost blind and no longer enslaved to the grandiosity of the specular, enraptured by the transience of modernity or concerned with the debt of representation. These recent oil paintings emancipate the space of painting and our encounter with it from the trappings of history and tradition. Light, air, water, colour and the enlivening materiality of oil paint itself provide symbologenic prisms in Bracha’s later works that initiate a journey across culture, history and art history by forming a connective tissue through time. This connective movement through time, and through art history, provides access to what I wish to term the “aesthetic unconscious of the artwork” that lies behind the surface of representation and opens onto a space-time for re-symbolisation that does not re-traumatise the feminine dimension of the subject. Rather than resisting the plane of representation, or refusing the formal demands of figuration, an inner space emerges from the painting process itself that ushers forth becoming-forms arriving from a space-time prior to the field of representation and figuration. I call the gathering of female figures drawn from myth, literature and biblical sources becoming–figuralities that ‘morph’ and apparate betwixt any singular canvas, transported by the evanescent ‘colour-light’ that cascades in aqueous, opalescent streams formulating a mesh in the space of the artistic’encounter-event’ that cannot be reduced to the plane of representation.* Elements of the paintings arrive in bundles, ribboning across canvasses in musical ensemble. An affective, subjectivising proto-abstraction emerges that disarms the eyes accustomed to technologies of representation to press upon and arouse excesses of those most gentle and merciful passions that are too often held in abeyance in the core of the human subject.

[i] Tina Kinsella (2015) ‘Sundering the Spell of Visibility: Bracha L. Ettinger ― Abstract-Becoming-Figural, Thought-Becoming-Form’ in Griselda Pollock ed., And My Heart Wound-Space. Leeds: The Wild Pansy Press, p. 283.

Fig. 9 Norham Castle, Sunrise (c. 1845) Fig.10 Bell Rock Lighthouse (1819)

Oil on Canvas Watercolour Gouache and Scraping Out on Paper

J. M. W. Turner J. M. W Turner

Fig. 11 Water Lilies, Nymphéas (after 1916)

Oil on Canvas

Claude Monet

As the sorrow evident in the Madonna of the Pietàs surfaces the delicate, sensitive, emotive force of páthos in the human by way of an appeal to our aesthetic sensibilities and susceptibilities, so too does the figure of the Madonna della Misericordia. She appears in the paintings of artists such as Piero della Francesca and Jacobo del Fiore to resurface the capacity for mercy signified by the figure of Mary, the mother. Whilst the term Madonna della Misericordia is generally understood as Virgin of Mercy as the word misericordia derives from the Latin words misericors (mercy, compassion), miserere (to pity), miseriae (misery), but also cor or cordis (heart), perhaps a more literal translation, my lady of the merciful heart, would be very meaningful here. Offering shelter to a group of people beneath her outspread mantle, this Madonna extends motherly love and compassion to a community beyond sanguineous family bonds. In Bracha’s Pietàs the Virgin’s splayed mantle is transformed into a net, now composed of transparent colour-lines and strobing fronds that rupture the surface of the canvas to form what I wish to term a becoming-porous membrane through which the viewer can enter what Christine Buci-Glucksmann has called the “inner space of painting” to bear the overwhelming sorrow of suffering and to carry the space for mercy and compassion.[i] An artistic space of encounter opens that provides routes for aesthetic, sublimatory passageways for trauma, horror, collective remembering and healing by exposing us to and revealing within us the originary páthos of loss, but also of ‘maternal shocks’ registered in the feminine aspect of the human. The infiltration of strobing paint is colour-becoming-musical as white light to excavate an artistic space capable of weaving shamanic invocations between series of Bracha’s paintings to transform the encounter with the artwork into a time-space of care.[ii] Here the horror and sorrow of the return of trauma is transformed, mysteriously alleviated by what I wish to term “maternal tendresse” that breaches the field of representation and figuration to index access to an inner ‘depth-space’. Our ‘touching gaze’ is enlaced to form a connective tissue between artist, artwork, fragilized participant and a space of depth thus appears in contemporary painting with an aesthetics that emerges from the artist’s “touching gesture“, itself a part of her particular mode of abstraction.

[i] See Christine Buci-Glucksmann (1995) ‘The Inner Space of Painting’ in Bracha Lichtenberg Ettinger Halal(a)-Autistwork. Aix-en-Provence.

[ii] See Tina Kinsella (2014) ‘Painting the Feminine into Ontology: On the Recent Works of Bracha L. Ettinger’. Commissioned art catalogue essay for Medusa-Butterflyexhibitions of artworks by Bracha L. Ettinger at the Museo Leopoldo Flores (Toluca, Mexico)/Galería Polivalente (Guanajuato, Mexico). Available at: https://tinakinsella.wordpress.com/catalogue-essay-painting-the-feminine-into-ontology-on-the-recent-works-of-bracha-l-ettinger/ And Kinsella (2015).

Fig. 12 Madonna della Misericordia (1460-62)

Oil and Tempera on panel

Piero della Francesca

Fig. 13 Madonna della Misericordia (1370-1439)

Tempera on Panel

Jacobello del Fiore

‘I will write to you with my eyes, always’

In ‘Medusa’s Head’, Sigmund Freud suggests that the mythic figure of the Gorgon, Medusa, is an unapproachable ‘symbol of horror’ who ‘repels all sexual desire ― since she displays the terrifying genitals of the Mother.’[i] In one fell swoop, the impassive stare of the Medusa that ‘makes the spectator stiff with terror, turns him into stone’ is conflated with the castration anxiety induced by the metonymic return of our archaic maternal origin. As evidenced in his analytic proposition of “the uncanny”, Freud suggests that the male child must separate from the mother to become a desiring subject in the first instance. In his ruminations on the Gorgon’s head, the Medusa is placeholder for mother and the mother signposts towards the Medusa, thus a dyadic loop is established between these two female figures which signal psychic disintegration for the subject and must be refused. The clustering female figures in other paintings from the period of the last 15 years by Bracha, such as Ophelia and Eurydice No. 1 (2002-2009), Eurydice, The Graces, Demeter (2006-2012), Eurydice, The Graces, Persephone (2006-2012), Medusa (2012) and Madusa and Owl (2012), hinge upon the theme of maternal rejection, abjection and perhaps even the madness outlined in Freud’s theses by way of an interminable return of the repressed mother-figure that Freud displaces into uncannily animated containers and automatons. Bracha’s paintings support alternative sublimatory routes or passages for uncanny anxiety than those elaborated by Freud. The routes that are elevated here do not depend upon the rejection and the repression the maternal figure. To approach the alternative modes of sublimation offered in Bracha’s recent oil paintings as well as by her theory, I feel the necessity to take a détournement through two works of Frida Kahlo: Henry Ford Hospital, and My Birth which were both executed in the year of 1932 during which the artist suffered the loss of a pregnancy and the loss of her mother. Bracha’s paintings and concepts have invited me to analyse these remarkable works in a new light

[i] Sigmund Freud (1977) in Werner Hamacher and David E. Wellberry ed., Writings on Art and Literature. Stanford: Stanford University Press, p. 265.

Fig. 14 Henry Ford Hospital (The Flying Bed) (1932)

Oil on Metal

Frida Kahlo

In these works, Kahlo’s visage portrays the implacable, stony gaze emanating from the mask-like face we are accustomed to seeing in her “autorretratos”. However, relaying the trauma of her recent miscarriage, Henry Ford Hospital transforms Kahlo’s usually intractable countenance. Tears spout from her eyes, like an unshored fountain. These tears are echoed in My Birth which captures the event of her mother’s death as well as the artist’s imagined birthing as a dead baby which is twinned with the loss of her mother into one monstrous tragedy. Aloft over the death bed, that is placed in the centre of the frame, hangs a painting within a painting of the Madonna Dolorosa (Our Lady of Sorrows) and it is she that weeps copious tears for the dead duet of mother and child. As ever, with Kahlo’s unique imagination we are never in the realm of representation as re-presentation, but of allegory and symbol that braid a profane parable. When Bracha’s Eurydices, Ophelias and Medusas assemble in the space of artistic encounter with her Pietás, we are also in conference with Kahlo’s symbols and allegories of irrecuperable loss and irreconcilable lament. Clearly the watery atmosphere of the cloudy space refers to a maternal womb not less than to the cosmos or the ocean and relates to the artist herself: her own miscarriages, abortion and pregnancies. Life matters that participate, according to her notebooks, in the elaboration of the symbolic Matrix.

Fig. 16 Ophelia and Eurydice No. 1 (2002-2009)

Oil on Canvas

Bracha L. Ettinger

Fig. 17 Eurydice, The Graces, Demeter (2006-2012)

Oil on Canvas

Bracha L. Ettinger

Fig. 18 Eurydice, The Graces, Demeter (2006-2012)

Oil on Canvas,

Bracha L. Ettinger

Fig. 19 Eurydice, The Graces, Medusa (?)

Oil on Paper Mounted on Canvas

Bracha L. Ettinger

Fig. 20 Ophelia, Medusa No. 1 (2006-2013)

Oil on Paper Mounted on Canvas

Bracha L. Ettinger

Fig. 21 Medusa (2012)

Oil on Canvas

Bracha L. Ettinger

Fig. 22 Madusa and Owl (2012)

Oil on Canvas

Bracha L. Ettinger

Whilst we rendezvous with the indexical trace of the Pietàs of Bellini, de Morales and El Greco and the Madonna della Misericordias of della Francesca and del Fiore, we also encounter in Bracha’s works since the early 2000s the monsters that proliferate through Francisco Goya’s prints and the existential, psychical monstrosity that permeates his Pinturas Negras (Black Paintings). Like Kahlo, Bracha creates with her own nightmares. Here, floats the spectre of madness and the long shadow of terror announced by the appearance of Ophelia in the water and the Medusa of the water, for Ophelia’s psychical disintegration is never more ominously proximate in the inner space of Bracha’s paintings than when she is accompanied by the treacherous tentacles and the silent scream of the death-inducing Gorgon, Medusa. Bracha’s Medusas are in the water. Red and ashen waters, steam or abyss, white, violent or purple airy waters are beside the figures floating from below or above.[i]

[i] See Bracha L. Ettinger (2001) ‘The Red Cow Effect’ in Mica How and Sara A. Aguiar ed., He Said, She Says. London: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press and Associated University Press.

Fig. 23 What more can one do? (The Disasters of War 33) 1812-15

Etching and Wash

Francisco Goya

Fig. 24 Atropos or The Fates (1820-23)

Mixed Method Mural Transferred to Canvas

Francisco Goya

Fig. 25 The San Isidro Pilgrimage (1820-23)

Mixed Method on Mural Transferred to Canvas

Francisco Goya

In her recent theoretical work on the Demeter-Persephone Complexity, Bracha has outlined three psychical zones that she entitles “Shocks of Maternality” that cannot be recuperated by uncanny anxiety, which cannot entirely disappear by primary repression and which are not subject to the Law of Oedipus that authorizes, after all, the identification between father and son:

A. Pre-maternity and Pregnancy (miscarriages, abortions, processes of adoption, barrenness, and variations of pregnancy). B. Birthing. C. Traumatic and phantasmatic losses and separations during motherhood from birthing to old age.[i]

Though these three zones of maternal shock are non-pathological in their essence, in Bracha’s view, the first two have been pathologized by a culture which can only recognise the traumatic affects and anxieties these shocks produce, such as uncanny anxiety, and the third one is mostly left unrecognized. Pathologized belatedly, the aesthetical and ethical primary arousals enlivened by the ‘Demeter-Persephone Complexity’ are not generally cognised or recognised as a shock to the mother and a trauma to the threads of the encounter-event in her psychc space. In Bracha’s Ophelia and Medusa works, the spectre of madness signalled by the stony-faced Medusa’s visage is transformed by the passage of tears as colour-water which ruptures the field of representation to harvest and glean a holding or container space for the silenced shocks of maternality. Pre-maternity to pregnancy, the passage of not-yet-life in the womb to perhaps life, perhaps non-life, from losing or birthing to the future spectre of the mother’s loss, to the death of a child, are held in the space that the serialisation of different grouped paintings creates. Bracha’s artworks cannot be considered in isolation, nor as repetitive serialisations. Rather, they are musical variations that weave webs and invoke shapeshifting initiations through the history of art, across and beyond time to forge conduits for the feminine: past, present and future. The maternal stratum in the subject which indexes the mother-daughter relation whose imprints and traces remain in each and every subject is re-enlivened. And it is through the engendering of symbologenic maternal devices that are occasioned between the paintings that the spectre of the mother as monster is “ameliorated”. By way of the apparition of these other figuralities in the feminine that join one another, the spectre of the archaic mother returns to solicit the child in us and awaken its care and offer it a symbolic relief. This occasioning initiates modes of what I term feminine mythopoetic genesis which is generative for non-pathological sublimatory passageways that grant access too and passage through shocks in the matrixial and maternal stratum of the subject.

In Alone of All her Sex, Marina Warner suggests that the tears of the Madonna Dolorosa ‘flow from the body, but unlike everything else from that source, they are not considered polluting.’[ii] In fact, the Madonna’s tears ‘are thought of as pure, like water. And it is within this complex and overarching symbolism of water that the weeping statues of the Virgin find a marginal place’.[iii] Quoting from Mircea Eliade, Warner observes that these waters:

… symbolise the entire universe of the virtual; they are the fons et origo, the reservoir of all potentialities of existence, they precede every form and sustain creation … Emergence repeats the cosmogonic act of formal manifestation; while immersion is equivalent to a dissolution of forms. That is why the symbolism of the waters includes death as well as rebirth.[iv]

The watery tears of the weeping Virgin contain and sustain the ambiguity of paradox. The conundrum of creation indexed by the manifesting of form from dissolution, that water suggests, signposts towards the mystery of birthing where joy and sorrow skirt in close proximity to potential death. During the act of birthing, a perilous encounter erupts between mother and child as the sustenance of both lives are at stake through the act of delivery that evacuates the infant from the maternal womb by way of the expulsion of the buoyant maternal waters in which it was previously carried. Water, then, is also darkness: an impenetrable crypt often countenanced as a place of impossible, terrible return whose mysterious tendrils reach back to our emergence from the amniotic fluid of the maternal womb. Water as carrier of life into life, is also bearer of the prehistory of the feminine in the subject and therefore it is to water we must return to stitch the feminine in the subject back into the history of thought so that womb does not signify tomb. The maternal voice is closely aligned with the womb as watery tomb. At all costs, the male ear must become deaf to that first maternal voice and this is why Odysseus must stop up the ears of his crew and bind himself to the mast of his ship as it sails through the channel of water guarded by the Sirens of ancient myth. The Sirens were the emissaries of Demeter and the song they sang was a lament for her abducted daughter, Persephone. The voice of the Siren bird-women calling men to a watery death signals that fear of an unthinkable return to the maternal body. As Luce Irigaray remarks:

… the voice of a human or a bird, as the music of the wind, never divides from the material place where it rises … the vocal message is made with the body itself and printed on the body which remains the place of memory.[v]

Irigaray observes that the ear, rather than the eye, is associated with the feminine, most especially in ancient religious rituals where music is more important than words. This is because “the ear which listens-to favours a becoming more fluid than the eyes which look at”. Which is why the mermaid in René Magritte’s The Collective Invention (1934) is mute, reduced within a phallic economy to the most meaningful gesture of her physical form: her genitalia. Half-fish, she has no ears to hear, no voice to speak. As Marina Warner observes in a chapter entitled ‘The Silence of Daughters’, the ‘muteness of women and daughters’ in myth and fairytale is specifically embodied in the characters of the Little Mermaid and the Sirens.[vi] The Little Mermaid leaves her watery habitat, giving up her voice to become human and take her place in the economy of desire that operates on earth-bound space, just as the abduction of Persephone rents her from her childhood flowery bower to institute the daughter, now woman, into an economy of adult desire.

[i] Bracha L. Ettinger (2014) ‘Demeter-Persephone Complex, Entangled Aerials of the Psyche, and Sylvia Plath,’ ESC 40.1 (March 2014), pp. 7-8.

[ii] Marina Warner (1983) Alone of All her Sex: The Myth and the Cult of the Virgin Mary. New York: Vintage Books, p. 222.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Mircea Eliade (1960) Images and Symbols ― Studies in Religious Symbolism, Translated by Philip Mairet. New York, p. 151.

[v] Irigaray, L.uce (2004) ‘Before and Beyond Any Word’ in Luce Irigaray: Key Writings. London and New York: Continuum, p. 135.

[vi] Marina Warner (1995) From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairytales and their Tellers. London: Vintage, p. 405.

Fig. 26 The Collective Invention (1934)

Oil on Canvas

René Magritte

The Sirens, in turn, use their voice (as song) to lure desirous men to a watery grave. In elliptical ways, both the Little Mermaid of fairytale and the siren of classical myth embody ‘the configuration of voice, fate and eros’ that threatens the loss of identity signified by the ‘in-between-ness’ of birthing whose indices emerges betwixt land and sea.[i] Warner observes that the:

… coupled image of voice and water also connects with another face of bliss, which may also have its being outside history, in the memory of the haven of the womb, and in the first sounds of the mother’s voice, that acoustic mirror. Fairy tales attempt to restore its resonance; they pretend to a world of nursery certainties. But they also often record that voice’s obliteration, and never more so than in the tales of silenced mermaids.[ii]

The silencing of women, but furthermore the feminine aspect of the subject, is formally announced in the Apollonian takeover at the site of the Delphic Oracle in ancient Greek myth. The mantic incantations of the Pythic Oracle at Delphi prophesied the most important future events: wars, ecological disasters, political action. Originally, her authority to speak the future came from the earth, from Ge, from Gaia, the female water serpent/dragon whose energy inspired the Pythia’s incantations/invocations. But water is formless: structure must be imposed. And so, Apollo — that god of the intellect, the mind, the rational faculties — staged a coup, killed the female water serpent, and henceforth the prophesies of the Pythia were exported from ‘mamalangue’ to papalangue.[iii] However, as Nicole Loraux and Paula Wissing note, this feminine time of origins that is subject to an Apollonian coup is no more than a creation myth for the instantiation of patriarchal authority and they ask: ‘What if this “history” were a trick, myth’s very deception?’.[iv] Loraux and Wissing suggest that:

The feminine had to be vanquished, neutralized with the help of legend. There is more than one site in Greece where this story can take place, but none is more applicable than Delphi, womb of the earth and navel of the world.[v]

However, Apollo’s usurpation of Delphi is never complete for the serpentesque Pythia’s mantic utterances, chants and incantations continued to contaminate distinctions between logos/speech and phōne/voice. Forthwith, Pythia did not simply ventriloquise the logos of Apollo; she did not only throwhis word forward. Rather the Pythia’s oracular interventions performed a ventriloquism that resonates with the Latin, ventriloquus, meaning to speak from the belly. The Latin is patterned upon the Greek engastrimythos, which literally means “speaking in the belly”: speech in the belly issued forth through mythos which is delivered by the mouth. The Pythia’s speech is an internal speech, externalised through the voice. Before Apollo, her mantic seat was a gift bequeathed to her through maternal succession at this place called Delphis which is, after all, the Greek word for womb. And this is why she understands the speech of the mute and hears the voiceless, because her prophesies are steeped in White Ink. They come from the mother’s voice, as first voice, sound (phōne) before logos (word). The Pythia is seated beside the Omphalos — the stone symbolising the navel of the world — and her speech is in the belly. It is a womb-voice attaching an umbilical cord, by way of the navel, to the ear. Bracha’s revolutionary theory of the Matrix, to which I will attend towards the end of my paper, reconceptualises the womb outside of the patriarchal parameters and establishes its symbols around the real of the ‘encounter-event’ of ‘jointness-in-differenc/tiation’, ‘metramorphosis’, ‘copoiesis’, ‘borderlinking’, ‘in between I and non-I’.

[i] Ibid, p. 406.

[ii] Ibid, p. 407.

[iii] ‘Mamalangue’ references the series of works by Bracha L. Ettinger of the same name. Jean-François Lyotard has conversed with this phrasing by Ettinger to develop the phrase ‘masalangue’. See Lyotard (1995) ‘Diffracted Traces’ in Bracha Lichtenberg Ettinger Halal(a)-Autistwork, Jerusalem: The Israel Museum. “Papalangue” is the word I develop for the purposes of this enquiry.

[iv] Nicole Lorraux and Paula Wissing (1995) The Experiences of Tiresias: The Feminine and the Greek Man. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, p. 184.

[v] Ibid, 186.

Fig. 27 Mamalangue No. 6 (2014-2015)

Oil on Canvas

Bracha L. Ettinger

Fig. 28 Eurydice No. 54 (2015-2016)

Oil on Canvas

Bracha L. Ettinger

Water and the maternal voice, that would be distinguished in culture, find further commencement in Bracha’s recent oil paintings. Whilst water cascades in aqueous streams and rivulets in these works, we are also reminded of the chrysalis, conches and shells that populate other recent works and are executed with india ink, wash and watercolour. These protective structures transform maternal shocks and the uncanny anxiety that skirts close by. We are returned to the maternal water within which were buoyed to life, to the water that nourishes the earth and water as an element that extinguishes fire. Water, as light in different colours in Bracha’s work, redresses the elision of the feminine in the symbolic histories we inherit. Water morphs with the colour and light of those alarming female figures which proliferate the history of art ― Ophelia, Medusa, Eurydice ― and which now appear in Bracha’s work as jelly-fish and as ghostly figuralities that follow abstract-movements of air inside the conch and the butterfly’s movement in the air alongside tiny horizontal lines which invite passageways for a movement from trauma, through phantasy and sublimation, to a ‘matrixial gaze’. The porous, watery, colour frond forms in these recent oil paintings are maternal signifiers that forge sublimatory routes to a space-time prior to the violent economies of sacrifice that find a placeholder in the paternal signifier and the myth of Oedipus: a move from sacrifice to com-passion.[i]

[i] See Bracha L. Ettinger (2006) ‘From Proto-Ethical Compassion to Responsibility: Besideness and the Three Primal Mother-Phantasies of Not-Enoughness, Devouring and Abandonment in Athena (2006, 2,).

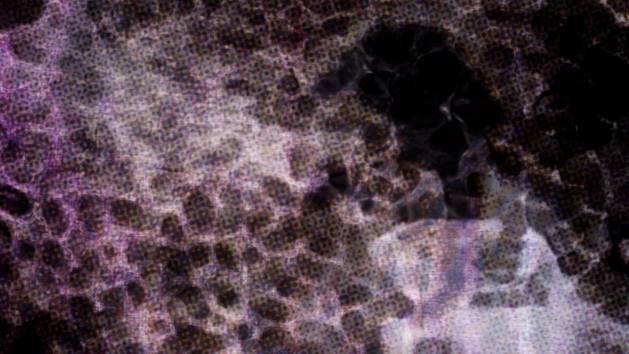

Figs. 29-36 MaMemento Fluidus ― MaMedusa (2012), [2014]

Video Stills

Bracha L. Ettinger

Iconography and abstraction become symbologenic through the provision of access to aesthetic modes of working-through horror, loss, grief, terror and fear by way of providing aesthetically attenuated psychical and corporeal aerials, ‘aerials of the psyche’, to access compassion and enliven hope. The field of contemporary visuality is no longer consigned to the unceasing repetition of trauma, and the surface gains a new ‘depthspace’. New sublimatory routes open by way of an appeal to the indexical reach of the aesthetic unconscious of the artwork that expands in the inner space of painting and its ‘matrixial borderspace’ to write to us through its eyes now informed by a conjugation of corporeal and psychical experience and affect. This is a movement between trauma and healing that opens a route for feminine sublimation in all subjects via the indexical link to tears, to water, and to the amniotic fluid and the womb-space from which we are all birthed.

Fig. 37 The Holy Family with the Butterfly (or Dragonfly) (1495)

Engraving

Albrecht Dürer

As literary, mythic, and biblical figures assemble alongside Eurydice in Bracha’s later works, I am reminded of an engraving by Albrecht Dürer entitled The Holy Family with the Butterfly (or Dragonfly) (1495). In the Christian faith, the butterfly is a symbol for the soul due to its transformation from the chrysalis, to caterpillar, to butterfly. For ancient cultures, the butterfly was a symbol of ancestral protection that signals self-transformation. For the Native American Pueblo tribes, the butterfly forms part of the creation myth. It was believed that the creator took the most beautiful colours and placed them in a magical bag which was handed to the children. When the children opened the bag, glorious butterflies flew out singing. For the Blackfoot Native American’s, the butterfly brings dreams to us in our sleep and women embroider the sign of a butterfly onto a piece of animal skin and tie it to their baby’s hair to help the child rest. In Bracha’s video piece, MaMemento Fluidus ― MaMedusa (2012), butterflies appear to hover over filmic frames depicting the artist’s aged and dying mother as well as hovering over the artist’s eyes in a stilled image of herself as a younger daughter. These butterflies are transformations from the Medusa-discs-chrysalides that hover over the eyes of the artist’s mother as a young woman in this video-piece, only to de-crystalise and soften into fragile butterfly-wings and to float in watery pages from Bracha’s notebooks which also appear in the filmic frames as watery passageways. The butterfly here begins to signal a feminine dimension of subjectivity that is passed from the mother to the child during pregnancy and birth, and which remains in the child to persist in the adult daughter or son after birth. As relayed by Nicole Loraux, this feminine aspect in each and every subject conveys the capacity for mourning and lamentation through the passage of tears. The tears which stage their entry in Bracha’s oil paintings as water, as amniotic fluid, carry and contain maternal grief and sorrow which, being taboo, is subject to societal regulation. But these paintings also provide a carry-space for compassionate maternal mercy. The gathering of all these figures for the feminine in the subject open a ‘depth of the painting’s inner space’ that:[i]

… doesn’t depend on the content “told” by the image that appears in a painting of in a series of paintings. A space is not its description either … The painting itself as a new image-body-matter activates a space in itself and in me. A subject appears. It can leave.[ii]

The depth of space that appears in the painting is not ‘triggered by the opticality of the imaginary’; rather the depth and space appear as a force field arising in the psyche from the margins of culture to enliven the possibility for a relief of its sublimation as revelation from which other meanings, beside and beyond those already embedded in familiar iconographies, can be transmitted and transformed.[iii] The aim, perhaps, is to rehabilitate our ethical sensibilities towards compassionate and merciful responsivity to those who are still living, or dead, with respect to the unique conditions of their suffering outside of any given interpretation that might be offered from the perspective of any individual mythical, literary or doctrinal context. The artist calls this ‘response-ability’. The encounter with art open us onto the wounds of the world, to experience the horror and sorrow of others, in ourselves, through the complex interweaving of beauty and sublimity that apparate in the inner space of painting via the aesthetic unconscious of the artwork.

In her diary, Kahlo wrote to her friend Jacqueline Lamba ‘‘I will write to you with my eyes, always. Kiss xxxxxx the little girl ….’. This inscriptive writing situates the little girl in Kahlo as an artist who sees the young girl as artist in her friend. Bracha’s paintings write to us with her eyes to appeal to the artist in us that is aroused when we accept the invitation that arises from her painterly process to consider that most primary aspect of our subjectivity as aesthetic sensibility by way of a donation of affect to the human that is formed by the ‘transcription’ and the ‘transcryption of/from’ our most profound emergence from the maternal womb ‘with-in’ the body of an other, a pregnant woman. This reframing of our understanding of the human subject situates the body as a site of experiential knowledge that announces “unsymbolised” corporeal experience that may be resistant to language, but which can find its way into our syntax, our lexicons, via the aesthetic encounter with the artwork.

‘And the Mother’s Case, Dismissed’

… in art, repetition in amnesiac working-through does not establish the lost object.

Rather, they make present the unrepresentable Thing,

crypted in the artwork’s unconscious,

that keeps returning because its debt can never be liquidated.

(Bracha L. Ettinger, ‘The Heimlich’)

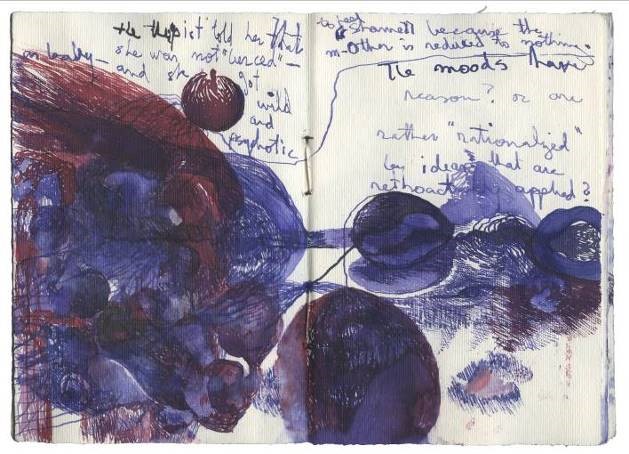

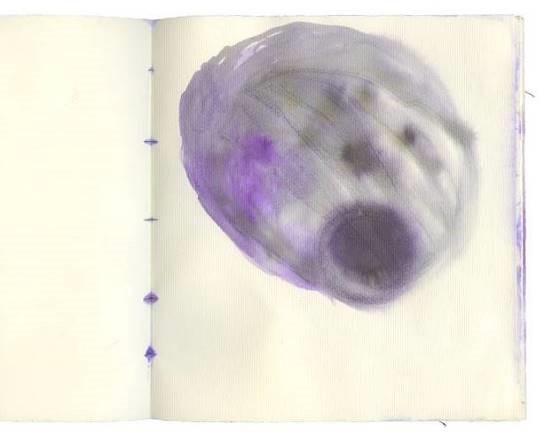

This knowledge of the voice that emerges from the subject carried in the amniotic waters of the womb is elaborated in the theory that arises from Bracha’s artistic process and practice into her theorywork. And this theory does not dismiss the mother’s voice, but rather rotates the Law of the Father’s word towards that ‘womb-space of co-emergence’ from which each and every subject is birthed. The seeds of Bracha’s theoretical writings are sown from her artistic and analytic practice during which some ‘lines, words, and fragments of sentences’ appear ‘around the painting’ or as a ‘residue’ of the painting and analytic process.[iv] These lines, words, fragmented sentences and residues conjugate in her notebooks by way of a painting-drawing-analytic-writing praxis as creatively blasphemous acts that challenge and trespass the limits of discrete disciplinary boundaries. Bracha suggests the ‘most graceful moments in the covenants’ between art and theory ‘occur when theoretical elements, only indirectly or partly intended for particular works of art, and visual elements which refuse theory, collide’.[v] During this covenantal collision between art and theory the ‘borderline between the two domains’ is transgressed and the double figure of artist-painter and artist-theorist emerge: theory may absorb aesthetic inferences from artistic processes and so take new meanings and art is momentarily touched by theory whilst certain visual elements from the artwork may resist being theorised.[vi]

Such a constellation between practices of painting and theorising moves beyond philosophical conceptualisations of aesthetical expressivity or ethical responsibility. Rather, the work of art and our encounter with it, is suggested as a threshold space where the aesthetical and ethical converge to reveal that beauty and sublimity emanate from and are, indeed, energised by a foundational compassion that is aesthetic, even though ‘beyond the senses’ at first. This compassion generates an innate facility for proto-ethical responsivity, ‘response-ability’, which provides the support for the ability to respond ethically; suggesting that by way of the matrixial sphere response-ability resides within the very core of the humane within the human being.

[i] Bracha L. Ettinger (2015) ‘And My Heart, Wound-Space With-in Me. The Space of Carriance’ in Griselda Pollock, ed., And My Heart Wound Space. Leeds: The Wild Pansy Press, p. 355.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Bracha L. Ettinger (2001) ‘Working-Through: A Conversation Between Craigie Horsfield and Bracha Lichtenberg Ettinger in Catherine Zegher ed., Bracha Lichtenberg Ettinger: The Eurydice Series, The Drawing Papers, No. 24. New York: The Drawing Center, p. 37.

[v] Bracha L. Ettinger (1993) Matrix Borderlines. Oxford: Museum of Modern Art, p. 38.

[vi] Ibid.

Figs. 38-40 White Notebook

Bracha L. Ettinger

The Ettingerian recalibration of our understanding of the human subject moves beyond classical philosophical and psychoanalytic models of subject formation which insist upon the individual within its anatomy and also on its intersubjective relation between self and other as the singular route towards subjectivisation. ‘Matrixial transubjectivity’ and ‘copoiesis’ are different from the model of intersubjective relationality. Privileging intersubjective relations between singular and separate individuals as a model for subject formation, Bracha L. Ettinger suggests, is a rationalised, phallic model that authorises the sovereignty of the male subject by banishing pregnancy and birthing from any contribution to subjectivisation. Establishing a non-phallic mode of subject formation, she proposes that ‘non-conscious, preconceptual and pre-identitarian’ subjectivisation processes commence before birth by way of aesthetic transmissions and affective attunements exchangedduring the late intrauterine encounter between the pregnant woman and not-yet-born infant.[i] As both men and women issue from the maternal womb in their very first instance, these primary affects remain as a potentiality for both sexes, regardless of gender, identity, or sexual practices and choices. Rotating our understanding of the human subject towards the feminine as a primary and originary subjectivising agency, Bracha invites us to consider that the shaping of our subjectivity is formed by that most profound emergence from the maternal womb in the body of a pregnant woman. And from this perspective, the hard-wiring of our subjectivity relies upon a relation of co-emergence and co-becoming between the not yet-born infant (becoming-subject) and the gestating woman (becoming-mother) who is an almost-alterity (Othereity) that is always, already impressed within any and every human being.

Alongside her articulation of the Demeter-Persephone Complexity that indexes shocks in maternal subjectivity, Bracha identifies a paternal complex that hides behind Oedipus which continues to circulate in the psychic and social field and which she entitles the Laius Complex which does not enter triangulation through the typical family dynamic of father, mother and child. This is a dyadic complex that speaks of a fatal delirium that can hit the father-son relation to enact a symbolic death on the son:

This unique son is dangerous to me, he must be sacrificed to calm down some not-yet yet as-if symbolic paternality in a dyad that no m/Other can guess. The betrayal strike is enacted under Law fulfilling mask. Laius hides himself behind some symbolically sustained paternal masquerade offered to the community.[ii]

Whereas Laius stands-in for destruction, Bracha L. Ettinger suggests that in the Oedipus myth, the shepherd is the ‘one who, like the infant’s mother preceding our birth, carries’.[iii] As carrier, the shepherd ‘feel-knows’ some ‘secret that mothers, birthing or not birthing, already know’.[iv] Indeed, the Greek mythological cycle is flooded with mothers who strive to intervene in a father’s sacrifice of his child: Jocasta saves Oedipus from his father (Laius), Clytemnestra cannot save her daughter Iphigenia from sacrifice at the hands of the father, Agamemnon. Ettinger argues that young mothers are ‘fragilized by the force of a sudden unexpected love’ by a ‘sudden and irremediable response-ability and responsibility, by the enormous trust directed toward them by the infant’ by the shock, sorrow and jouissance of their care-carry mode of com-passion.[v] Suddenly vulnerable they now face:

… a new reality, realizing their deep transconnectedness to the vulnerable other. The weight of this carriance-and-trust estranges them in a world lacking the language to account for it, where affects, different from anxiety yet with similar resonance, lack recognition or value; a world where trust already expects a betrayal. The recognition of the Symbolic matrix can intervene to stop the performance of a potential betraying agency, to awaken self-awareness to one’s such power. This self-awareness is ethical. You shall not sacrifice the other. You shall not betray the trusting, vulnerable other. You shall be aware of your possible desire to perform a seduction into death and use your awareness to stop it.[vi]

The Symbolic matrix that Bracha references is the conceptual apparatus by which she thinks through the exchange of primary aesthetic and proto-ethical affects donated in the affective co-emergence which unconsciously informs the subject in a mode of ethicality in and for life. Recognition of the primary trust invested in the mother by the infant during and after birth enlivens a non-sacrificial economy that resists Laius and Oedipus. However, Bracha also recognises that other complexity which is feminine that operates alongside both the Laius and Oedipus complexes, suggesting that becoming aware of all these complexities will humanise the human.

[i] Ibid.

[ii] Bracha L. Ettinger (2016) ‘Laius Complex and Shocks of Maternality: With Franz Kafka and Sylvia Plath’ in Yochai Ataria, David Gurevitz, Haviva Pedaya and Yedal Neria eds., Interdisciplinary Handbook of Trauma and Culture, Switzerland: Springer, p. 281.

[iii] Ibid, p. 280.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid, p. 284.

[vi] Ibid.

Figs. 40-45 Ein-Raham – Eurydice III (2012), [2014]

Video Stills

Bracha L. Ettinger

The Demeter- Persephone Complexity emerges from the shock of pregnancy and birthing in the mother and is carried by the feminine in the subject, whether that subject is daughter or son. This complexity reveals the ‘intra-side of the mother Demeter’; her shock, phantasm, joy, trauma, sexuality and fragility is ‘echoed, not mirrored’ in the subject Persephone while the daughter’s trauma reverberates in the mother.[i] Painting and creativity forge circuits for the shock in the maternal-mother-infant encounter to be re-encountered so that ‘care-carry-carriance’ not only mediates the shocks of maternality but become the symbolic configuration that gives its pain in us a meaning. The figuralities of the feminine that stage their spectral appearance in Bracha’s recent oil paintings carry layers of the maternal shocks and of the shocks induced by atrocities done to women and children, whilst opening onto an expanded space of re-presentation that is now informed by the womb-space and available to the viewer as a subject-carrier who may bear the traces of trauma carried within the paintings inner space, if s/he fragilizes herself to be receptive to the residuals of pain.

Gathering, garnering, gleaning in a what I wish to call a recuperative gesture that is also reparative, the viewer-as-participant enters the wounded heart space of the painting that I entitle “the womb of the artworking process“. The part of the subject that enters the painting is not elicited by its representational demeanor, but rather by the grieving, sorrowing and joyful psychical kernels in the “porous membrane-space of the painting” that connects to that most humane aspect at the core of the human.

Bracha L. Ettinger offers the concepts of ‘wit(h)nessing’ and ‘carriance’ to identify the movement of the freight of trauma in the subject to the surface of culture to account for the potential access, and possibility dispersal, of that freight. ‘Wit(h)nessing’ signals a witnessing-with the traces of trauma in our others, even access to immemorial memories which may not be one’s own. According to Bracha, ‘conductible borderlinks’ between the artwork and the viewer-as-participant in that work can be co-produced.[ii] She calls this shared process artworking to explain the manner in which ‘the possibility for the transmission and dispersal of trauma’[iii] by way of ‘borderlinking-borderspacing’. Instances of ‘being-with’ are aroused by ‘uncognised threads and strings of trauma’ in the artwork that are ‘accesses to others’.[iv] ‘Carriance’ refers to the capacity to bear and thus also somehow care-for the traces of trauma that do not even “belong to oneself”. Through the process of artworking, the encounter with the artwork, and entry into the heart of the painting’s space, a subject-in-and-with-painting-space unfurls to carry and care for our present, ‘post-traumatic era’. The artist suggests that our ‘generation inherited and lives through-by-with-in a colossal requiem’.[v] ‘Carriance’ indexes ‘Trust after the end of trust’ that supports a linkage with ‘Trusted threads’ of psychic imprints through art as a space of transmission and ‘elaboration of traces of trauma.’[vi] Here the pain and joy of pregnancy, of labour, of birthing and being birthed is interlaced with the shadow of loss and the subsequent wounds heralded by the spectre of future loss. Bracha deploys the term misericordiality to denote emotion of the maternal womb which ‘echoes a relation of hospitality which is feminine by the exemplary way of the maternal womb and links hospitality to the absolutely future and to vulnerability’.[vii] In Humanism of the Other (1972), Emmanuel Levinas points towards an emotion ‘from the maternal entrails’ that he links to vulnerability.[viii] However, for Levinas, subjectivity commences after birth, in the domain of intersubjectivity where the subject is in relation to another understood as an absolute Other, an alterity. Therefore, the emotion he associates with maternal entrails and with vulnerability situates the feminine firmly on the side of passivity.

Ettinger rotates this phallic model of the subject to insist that subjectivisation commences, in is first instance, from the feminine, prior to birth, by way of the maternal ‘transconnectivity’ that is established between becoming-mother and becoming-infant during the late intrauterine encounter-event. In Bracha’ Ettinger’s model of subjectivisation, pregnancy is not relegated to a passive encounter-event during which the other is an absolute other to begin. Rather the m/Other, as Othereity, and becoming-infant are in a transgressive relation of co-emergence and the mother as subject contributes to the formation of subjectivity as such. Here, then, the term misericordiality indicates the capacity to reach back to our archaic maternal origins not in terms of regression to symbiosis but so as to evoke our capacity to ‘transconnect’ with and ‘com-passion’ [passioning together]alongside the vulnerability of the other in the demeanour of ‘besidedness’ by way of an act of ‘self-fragilization’ which indicates agency by signaling an agreement to fragilize oneself in an attitude of hospitable, co-emergent ‘subreal’ relationality. Misericordiality indexes the existence of a ‘kernel of ethical being’ donated by our encounter in the maternal womb and ‘cognizing’ the other and the world by way of “being-toward-birth’ that can be mobilised as an affective compassion and ‘transubjective response-ability’ that leads to ‘subjective responsibility’ to work through loss, horror, and trauma in life and to recognize the suffering of th other and the vulnerability of the earth. In this way, Ettibgerian misericordiality is concerned with the deepest level of subjectivity by way of having begun:

… before, and always also beyond, any possibility of empathy that entails understanding, before any economy of exchange, before any cognition and recognition, before any reactive forgiveness and integrative reparation.[ix]

This is because womb-misericordiality‘as pregnancy-emotion that stands for com-passionate hospitality’ in pregnancy and birthing and therefore it is also from birth a part of our journey towards life, from ‘non-life to life’.[x] For the artist, the way to achieve sovereignty over our body and the freedom to decide our fate and reach having the full rights over our own body passes through conceptualising every aspect of the female body and creating words and forms that give it a voice, words that describe a domain the the phallic law can’t dominate. Misericordiality relates to that which is indeed future, as Levinas would have it, but by reminding us and restoring to us, beyond our eventual corporeal perishability, the assailable condition of vulnerability and ‘self-fragilisation’ that brings about a new notion of ‘resistance and trust,’ and the future with a witnessing of the past.

[i] Bracha L. Ettinger (2014) ‘Demeter-Persephone Complex, Entangled Aerials of the Psyche, and Sylvia Plath’ in ESC 401.1 (March 2014): xx-yy, p. 288-9.

[ii] Bracha L. Ettinger (2006) ‘Weaving a Woman Artist with-in the Matrixial Encounter-Event’ in Brian Masssumi ed., The Matrixial Borderspace. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, p. 180.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Bracha L. Ettinger (2006) ‘Wit(h)nessing Trauma and the Matrixial Gaze’ in Event’ in Brian Massumi ed., The Matrixial Borderspace. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, p. 148.

[v] Bracha L. Ettinger (2015) ‘Carriance, Copoiesis and the Subreal’ in Griselda Pollock, ed., And My Heart Wound Space. Leeds: The Wild Pansy Press, p. 344.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Bracha L. Ettinger (2006) ‘From Proto-Ethical Compassion to Responsibility: Besideness and the Three Primal Mother-Phantasies of Not-Enoughness, Devouring and Abandonment in Athena (2006, 2,), p. 101.

[viii] See Emmanuel Levinas (2006) Humanism of the Other, translated by Nidra Poller. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, p. 64. In footnote 6 for this page, Levinas writes ‘We have in mind here the biblical term rakhamin, translated as “mercy” but bearing a reference to the word for uterus, rekhem; it means mercy that is like an emotion from maternal entrails.’

[ix] Ibid, p. 100.

[x] Ibid, p. 103.

Figs. 46-47 Ein-Raham – Crazy Woman (2012-14)

Video Stills

Bracha L. Ettinger

‘I was transforming my blood into comprehensive energy ― masculine and feminine, microcosmic and macrocosmic ― and into wine that was drunk by the moon and the sun’ (Leonora Carrington) [i]

Two drops of Gorgon’s blood

One is poisonous, the other cures disease

(Euripides, Ion)

Griselda Pollock, observes that ‘the invisible sexual specificity of the female body has a long metaphorical history in western thought, both fascinating and horrifying it.’[ii] This re-constructed phantasmatic feminine — fetishised by being either idealised or horrified — is the concept of the feminine that has often been historically re-iterated in western philosophical thought and culturally immortalised in western arts. However, in Bracha’s art, the feminine body, and most profoundly the maternal corpus, is re-approached as source of creativity and generator of the capacity to respond to art’s invitation.

[i] Leonora Carrington (1998) Down Below. New York: New York Review of Books, p. 21.

[ii] Griselda Pollock, ‘Thinking the Feminine: Aesthetic Practice as Introduction to Bracha Ettinger and the Concepts of Matrix and Metramorphosis’ in Theory, Culture and Society 2004: 2;5, p. 34.

Fig. 48 El Aborto (The Abortion, Miscarriage or Untitled) (1932)

Lithograph

Frida Kahlo

This is a cosmological medicine that chimes with the symbolism surrounding the blood of the Gorgon, Medusa, in ancient mythology, which was considered to provide a holding space for contradiction, being a carrier of both poison and cure. This cosmology is announced in a final work I wish to return to by Frida Kahlo: El Aborto (The Abortion) which she produced in 1932, the same year as Henry Ford Hospital and My Birth. This work is a symphony of dualisms that holds a space for contradiction by way of mediating between the personal experience of the artist and the transformative capabilities of the artist’s gesture. In this work, Kahlo is standing with her arms placed along her side. On her right side we see an image of the miscarried foetus. A third arm extends from her left shoulder, it carries an artist’s palette which is fashioned in the shape of a heart. Once more, the tears that flow from her eyes reference the recent loss of a pregnancy. Uterine blood from her emptied womb flows down her left leg and into the earth to nourish plants she has sketched beside her standing form. The drawing is a testament to the sublimation of the personal experience of pain and loss into art. Commenting in her diary, perhaps at some point later in time, Kahlo remarks that she ‘gave birth to herself’ through the act of painting by which she established herself as the artist.

Fig 49-51. Notebook (2013)

Bracha L. Ettinger

Finally, we can approach Bracha’s own personal experience which is also offered as a healing codex by which to re-approach the collective cultural inheritance of collateral trauma that the Eurydice series and her recent oil and paper work bear. These works communicate with the shellshock she experiences as a young woman of 19 in obligatory service some 50 years ago when, taken by surprise and without any higher order around, she began to organise the rescue operation of survivors from a destroyer shipwreck and led the rescue and evacuation operation of dozens of wounded and burned young men for many hours during the night in which she too was wounded when a helicopter that caught fire collapsed in her direction. The Israeli Eilat was placed under Egyptian missile attack on the 21st October 1967, with 199 crew members on board. Out of 147 young men who remained alive, 99 were injured. Most of them passed during the night in the improvised hospital that Bracha organised while she was also co-ordinating the rescue by air.[i] Bracha refers to her shellshock as fire and water shocks. The water motif began to resurface in her artworks since 2008, the more conscious theme of gasping appears via the Medusa paintings and the video-films in 2012, and the full-blown shellshock followed them, in 2013, leading to the Pietà series. If the experience of ‘fire and water shock’ are signalled already in the Ophelia series, Ophelia’s slow death by drowning can be seen retroactively through the Medusa’s watery fronds, coiled, serpentine hair and jelly-fish tentacles. The Medusa of 2012 can be seen retroactively via the lenses of the Pietà paintings that followed right after. These artworks also invoke bodies in the water, the bodies drowning in the water, amidst the flames emanating from the exploding shipwreck. Pietà and Medusa encounter Eurydice again. The Ettingerian Unconscious, as well as her painting and notebooks, is a “working pentimento, with the abstract principle of the spiral becoming conch”.

All these works press upon the experiences of three of Bracha’s maternal aunts: Helka, Etka and Saba (Fried) who survived internment at Auschwitz concentration camp and the death march to Stutthof camp, only for Helka to be drowned in the Baltic Sea. The evacuation of those imprisoned within the Stutthof camp system began on 25th January 1945. Approximately 5,000 prisoners were marched to the Baltic Sea where there were forced into the water and subject to machine gun fire. In April that year, the remaining prisoners were removed from Stutthof by sea as the camp was, by now, enclosed by Soviet forces. Helka was put into one of these rescue boats and drowned by direct fire. This familial history of horror skirts between and betwixt the psychical remnants of Bracha’s own traumatic experience of the recovery operation during which she was compelled to rescue all the wounded floating in the middle of the sea beside the burning and then sinking ship, and to bear the memory of the wounded bodies and imagine the gasping mouths of those who could not be recovered on that night with the light of the full moon streaming upon them, when she herself was suddenly frozen under danger. In an open letter addressed to her friend and collaborator, Griselda Pollock, Bracha writes:

… me, sitting on the asphalt, in front of the burning helicopter, my head between my hands, gazing at the flames, I cannot move … I felt and still feel in my hands. They curve the shape of the head between the hands and the open grasping mouth. The more I cover, the more I morph by lighting. The colours in dark to become light in light, become light. More to cover, more to uncover, more to discover, more to carry. The painting is doing all this. As the figures disappear, ghosts appear. The open mouth looks. It was a night of full moon. The moon was on the side of life. … the moon and the Medusa can also represent death and the mother.[ii]

How does one bear witness to such a litany of horror? How can such an impossible witnessing carry and care for (carry-care-for) the diffusion of traumatic traces with the hope of finding passageways for the kind of transgenerational healing that generations to come may yet need?

[i] For more information on the sinking of the Eilat destroyer ship, and Bracha’s role in the rescue and recovery operation see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FepDt4KniyQ&feature=youtu.be. Bracha met those men whose lives she had saved many years later. For more information, see: https://news.walla.co.il/item/3117827.

[ii] Received via personal correspondence between the author and the artist.

Fig. 52-54 Notebook

Bracha L. Ettinger

Subject-carriance and subject-space also finds webs of connection with and protective structures in the chrysalis, shells and conches that appear in appear in a figurative way and are insinuated by the abstraction in many of Bracha’s recent works on paper that signify the reawakening of shellshock in the artist, the bodies drowning in the sea by the wreck of the Eilat, the sea into which the artist’s aunt Helka was submerged and the watery graves into which the many refugees seeking sanctuary in our times capsize daily. The artist poses a pressing and urgent question:

We have to ask what kind of human subject and society was shaped in view of man’s lack of womb not as organ but in terms of lack of a whole symbolic universe of meaning and value.[i]

The value being copoiesis in bearing life but also death outside the phallic domain and control. A subject infused but also informed by the specificity of the feminine. In Our Time, right now, the persistent annihilation of swathes of people around the world — politically, symbolically, actually — continues alongside a perpetual desecration of the category of the human. This knowledge can be overwhelming, too much to bear. But this knowledge also provokes an ethical imperative to resist this desecration and to seek modes of imagining a world, otherwise. Such imagining elevates and enervates structures for political resistance informed by vulnerability and self-fragilization. In Bracha’s musical time-space of the painting when it is artworking, we are invited to share and participate in a sphere of care that connects past and present atrocity with the possibility of a future informed by the maternal aesthetical capacities and wounds that are, always already, installed within us, now ready to be taken into account in a new symbolic way. The futurity we imagine can be activated in the present, so that the fissure that has occurred between phallic economies of violence and sacrifice and the maternal economy of gestation-generation are no longer posed in opposition to each other, can now nourish transformation. The horror that flows, becomes frozen and mortify again from the maternal as ruptured can be sutured by the expanded subjectivity that we participate in on the maternal dimension of the subject. ‘To hallow the hollow’ does not mean to fill a lack but to grasp the intervals in depth. The painting works its depth via intervals created over time. The expanded subjectivity, thus conceptualised, cannot be reduced to any allegiance to particular ideology or community, for it is prior to the space that the Phallus occupies or controls, and it dwells beside it. We can return to a space of trust, before the “end of trust” that our present era signals. Bracha’s artworking informs her theoryworking which, in turn, can inform our social imaginary by way of an aesthetics that percolates from our affective sensibilities to infiltrate our thought and, ultimately, affect and effect our executive actions in this world.

Situating the maternal womb as a site of invention that evokes a space of co-emergence and agency is an intervention in the ceaseless, traumatic repetition of modernity and its aftermath, as Griselda Pollock remarked. The event and encounter (‘encounter-event’) of pregnancy that donates meaning to the human by forging a foundational aesthetical and ethical dimension within subjectivity provides a conceptual prism from which to radically rethink the ontology of social relations between self and other in each singular co-emergence The transgressive shareability (‘transjectivity’) Bracha outlines indexes a primary openness to the world that is shaped by our very first co-mergence from a female body. Here, we are in the domain of the deepest aspects of human subjectivity that remains connected to the feminine in the subject.[ii] This feminine is the ethical kernel in the human being that provides the ultimate measure of the ethical relationship as it transforms the subject, and what it is to be a subject, from within. Painting is a way to meditate on this kernel and find a ‘knowledge through resonance’ with it. As you wit(h)ness Eurydice, you access the knowledge of the chrysalis, conch, the Medusa, the butterfly, the ashes and the water.

* Please note that phrases which appear in quotation marks (’xxx’) but without direct citation throughout this essay, such as ‘morph’, ‘colour-light’ and ‘copoiesis’, etc., are concepts developed by the artist that are articulated across many.

** Please also note that phrases which appear in quotation marks (“xxx“) such as “maternal tendresse” are concepts developed by the author of this essay.

[i] Bracha L. Ettinger (2014) ‘Demeter-Persephone Complex, Entangled Aerials of the Psyche, and Sylvia Plath’ in ESC 401.1 (March 2014): xx-yy, p. 2.

[ii] See ‘Becoming Human: Bracha Ettinger and Griselda Pollock in conversation at Crunch 2011. Available at http://www.iai.tv/video/becoming-human. Accessed 16 February 2012 and Bracha L. Ettinger (2006) ‘Weaving a Woman Artist with-in the Matrixial Encounter-Event’ in Brian Massumi ed., The Matrixial Borderspace. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

1 Edmond Jabès in conversation with Bracha L. Ettinger (1993). ‘A Threshold Where We Are Afraid’ in the Museum of

Modern Art, 1993.

2 Nicole Loraux (1998) Mothers in Mourning. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, p. 11, p. 24 and p.25.

3 Ibid, p. 25.

4 Tina Kinsella (2015) ‘Sundering the Spell of Visibility: Bracha L. Ettinger ― Abstract-Becoming-Figural, ThoughtBecoming-Form’ in Griselda Pollock ed., And My Heart Wound-Space. Leeds: The Wild Pansy Press, p. 283.

5 See Christine Buci-Glucksmann (1995) ‘The Inner Space of Painting’ in Bracha Lichtenberg Ettinger Halal(a)-

Autistwork. Aix-en-Provence.

6 See Tina Kinsella (2014) ‘Painting the Feminine into Ontology: On the Recent Works of Bracha L. Ettinger’.

Commissioned art catalogue essay for Medusa-Butterfly exhibitions of artworks by Bracha L. Ettinger at the Museo Leopoldo Flores (Toluca, Mexico)/Galería Polivalente (Guanajuato, Mexico).

7 Sigmund Freud (1977) in Werner Hamacher and David E. Wellberry ed., Writings on Art and Literature. Stanford:

Stanford University Press, p. 265.

8 See Bracha L. Ettinger (2001) ‘The Red Cow Effect’ in Mica How and Sara A. Aguiar ed., He Said, She Says.

London: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press and Associated University Press.

9 Bracha L. Ettinger (2014) ‘Demeter-Persephone Complex, Entangled Aerials of the Psyche, and Sylvia Plath,’ ESC

40.1 (March 2014), pp. 7-8.

10 Marina Warner (1983) Alone of All her Sex: The Myth and the Cult of the Virgin Mary. New York: Vintage Books, p.

222.

11 Ibid.

12 Mircea Eliade (1960) Images and Symbols ― Studies in Religious Symbolism, Translated by Philip Mairet. New

York, p. 151.

13 Irigaray, L.uce (2004) ‘Before and Beyond Any Word’ in Luce Irigaray: Key Writings. London and New York:

Continuum, p. 135.

14 Marina Warner (1995) From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairytales and their Tellers. London: Vintage, p. 405.

15 Ibid, p. 406.

16 Ibid, p. 407.

17 ‘Mamalangue’ references the series of works by Bracha L. Ettinger of the same name. Jean-François Lyotard has

conversed with this phrasing by Ettinger to develop the phrase ‘masalangue’. See Lyotard (1995) ‘Diffracted Traces’ in Bracha Lichtenberg Ettinger Halal(a)-Autistwork, Jerusalem: The Israel Museum. “Papalangue” is the word I develop for the purposes of this enquiry.

18 Nicole Lorraux and Paula Wissing (1995) The Experiences of Tiresias: The Feminine and the Greek Man. New

Jersey: Princeton University Press, p. 184.

19 Ibid, 186.

20 See Bracha L. Ettinger (2006) ‘From Proto-Ethical Compassion to Responsibility: Besideness and the Three Primal

Mother-Phantasies of Not-Enoughness, Devouring and Abandonment in Athena (2006, 2,).

21 Bracha L. Ettinger (2015) ‘And My Heart, Wound-Space With-in Me. The Space of Carriance’ in Griselda Pollock,

ed., And My Heart Wound Space. Leeds: The Wild Pansy Press, p. 355.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

24 Bracha L. Ettinger (2001) ‘Working-Through: A Conversation Between Craigie Horsfield and Bracha Lichtenberg

Ettinger in Catherine de Zegher ed., Bracha Lichtenberg Ettinger: The Eurydice Series, The Drawing Papers, No. 24. New

York: The Drawing Center, p. 37.

25 Bracha L. Ettinger (1993) Matrix Borderlines. Oxford: Museum of Modern Art, p. 38.

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid.

28 Bracha L. Ettinger (2016) ‘Laius Complex and Shocks of Maternality: With Franz Kafka and Sylvia Plath’ in Yochai

Ataria, David Gurevitz, Haviva Pedaya and Yedal Neria eds., Interdisciplinary Handbook of Trauma and Culture, Switzerland:

Springer, p. 281.

29 Ibid, p. 280.

30 Ibid.

31 Ibid, p. 284.

32 Ibid.

33 Bracha L. Ettinger (2014) ‘Demeter-Persephone Complex, Entangled Aerials of the Psyche, and Sylvia Plath’ in ESC 1.1 (March 2014): xx-yy, p. 288-9.

34 Bracha L. Ettinger (2006) ‘Weaving a Woman Artist with-in the Matrixial Encounter-Event’ in Brian Massumi ed., The

Matrixial Borderspace. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, p. 180.

35 Ibid.

36 Bracha L. Ettinger (2006) ‘Wit(h)nessing Trauma and the Matrixial Gaze’ in Event’ in Brian Massumi ed., The

Matrixial Borderspace. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, p. 148.

37 Bracha L. Ettinger (2015) ‘Carriance, Copoiesis and the Subreal’ in Griselda Pollock, ed., And My Heart Wound

Space. Leeds: The Wild Pansy Press, p. 344.

38 Ibid.

39 Bracha L. Ettinger (2006) ‘From Proto-Ethical Compassion to Responsibility: Besideness and the Three Primal

Mother-Phantasies of Not-Enoughness, Devouring and Abandonment in Athena (2006, 2,), p. 101.

40 See Emmanuel Levinas (2006) Humanism of the Other, translated by Nidra Poller. Urbana and Chicago: University

of Illinois Press, p. 64. In footnote 6 for this page, Levinas writes ‘We have in mind here the biblical term rakhamin, translated as “mercy” but bearing a reference to the word for uterus, rekhem; it means mercy that is like an emotion from maternal entrails.’

41 Ibid, p. 100.

42 Ibid, p. 103.

43 Leonora Carrington (1998) Down Below. New York: New York Review of Books, p. 21.

44 Griselda Pollock, ‘Thinking the Feminine: Aesthetic Practice as Introduction to Bracha Ettinger and the Concepts of

Matrix and Metramorphosis’ in Theory, Culture and Society 2004: 2;5, p. 34.

45 For more information on the sinking of the Eilat destroyer ship, and Bracha’s role in the rescue and recovery

operation see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FepDt4KniyQ&feature=youtu.be. Bracha met those men whose lives she had saved many years later. For more information, see: https://news.walla.co.il/item/3117827.

46 Received via personal correspondence between the author and the artist.

47 Bracha L. Ettinger (2014) ‘Demeter-Persephone Complex, Entangled Aerials of the Psyche, and Sylvia Plath’ in ESC

401.1 (March 2014): xx-yy, p. 2.

48 See ‘Becoming Human: Bracha Ettinger and Griselda Pollock in conversation at Crunch 2011. Available at

http://www.iai.tv/video/becoming-human. Accessed 16 February 2012 and Bracha L. Ettinger (2006) ‘Weaving a Woman

Artist with-in the Matrixial Encounter-Event’ in Brian Massumi ed., The Matrixial Borderspace. Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press.